How "Fake" Fossils Have Real Value

/If you had to guess, would you say that this is a real fossil, or a reproduction? This is one of the specimens soon to be on display at the Bruce Museum for the upcoming Secrets of Fossil Lake exhibition. As you might have guessed, it is a snake skeleton. As you may not have guessed, it is a reproduction.

In a previous post, I touched on one of the reasons why making reproductions of fossils is useful. Fossils can be very heavy and lighter casts are easier to transport. However, this is not the only way in which fossil reproductions are used.

Photo by H. Raab

This fossil of Archaeopteryx is famous for illustrating the transition between dinosaurs and birds. It is highly recognizable and often features in biology textbooks on the subject. This fossil is located in Berlin, Germany but you can find reproductions of it in many museums and classrooms across the world. By duplicating a fossil, the educational value of that fossil is also duplicated. I've even used a cast of this fossil when teaching biology labs!

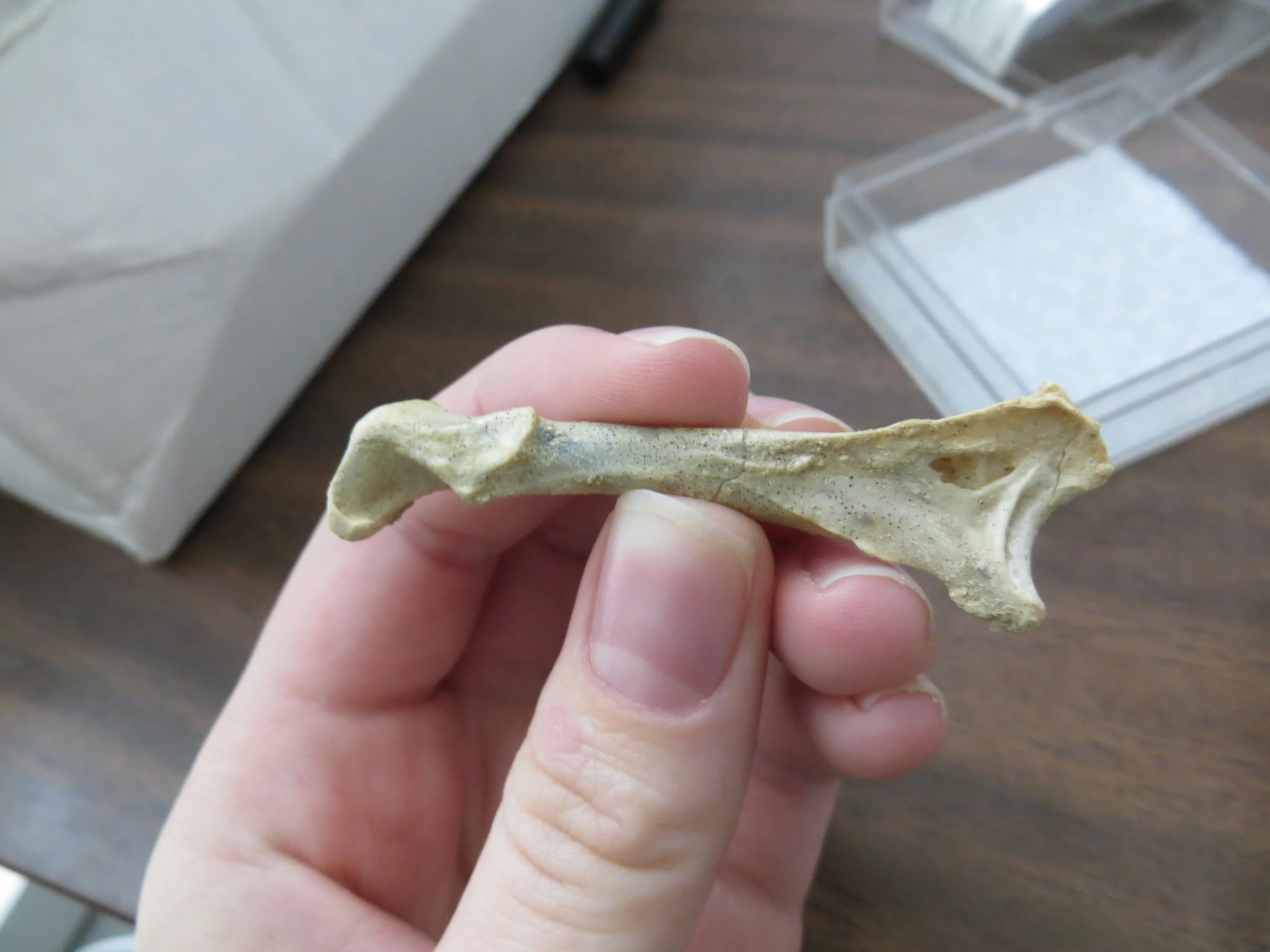

Reproductions tend to be superior to the original fossils in terms of durability. In this picture, I'm holding a bird fossil. I'm holding it very carefully, because fossils can be exceedingly delicate. If I had dropped this fossil, it would have likely broken into several pieces. Using fossil reproductions takes away the danger in handling scientifically valuable and fragile specimens. Fossil reproductions are invaluable for educational purposes when the original fossil may not be durable enough to be handled by large groups.

There is a particularly prominent line near the top part of this image, underneath the darkest band of bone. These lines are called "lines of arrested growth" and are a record of a time when the animal stopped growing, such as over winter when resources were scarce.

Photo by Kate Dzikiewicz

The final reason why reproductions are valuable is less intuitive. The photo above is an image of bone microstructure in an early crocodile relative. You may notice lines cutting horizontally across the bone. Like rings in a tree, counting these lines let scientists know how old an animal was when it died and how fast it might have grown.

This is a fascinating research subject, but it comes at a cost. It is only possible to get these images by taking thin slices of bone from fossils. This is called destructive sampling, because it harms fossils for research purposes. In order to preserve the original structure of the fossil, reproductions are made prior to any destructive sampling. This way, researchers can benefit from destructive sampling while making sure that future generations know what the fossil looked like before.

Here is a reproduction we recently received for Secrets of Fossil Lake. It is a cast of a Borealosuchus fossil, an ancient species of crocodilian, but it would be hard to tell that just by looking at it. Museum-quality fossil reproductions aren't complete until they receive a coat of paint.

Sean Murtha is in charge of painting Borealosuchus. For the last week, he's been hard at work in our collections, carefully matching our reproduction to the colors of the original fossil. He isn't finished yet, but already the places he's painted look far more realistic than the unpainted original.

No detail is too small for Sean. This fish fossil was found near the foot of Borealosuchus. The fish is faithfully restored in our reproduction, so visitors will be able to see what sort of animals lived and died alongside Borealosuchus. A truly excellent fossil reproduction will be nearly indistinguishable from the original.

Painting a fossil is even more difficult than it sounds. Crocodilians are covered in protective bony plates called osteoderms.The pitted surface of osteoderms make them challenging to color.

This is a reproduction of an early mammal from Fossil Lake. The skeleton looks convincing after being painted and the addition of rocky background colors will soon complete it.

While we do include real fossils in our displays, fossil reproductions are an important part of exhibits. Reproductions allow for fossils to be used in more versatile ways than could be done with the originals. Stop by the Secrets of Fossil Lake exhibit from November 21, 2015 through April 17, 2016 and see for yourself how challenging it can be to tell real from reproductions.

- Kate Dzikiewicz, Paul Griswold Howes Fellow