Fossilizing the Footsteps of Dinosaurs

/Photo by Kate Dzikiewicz

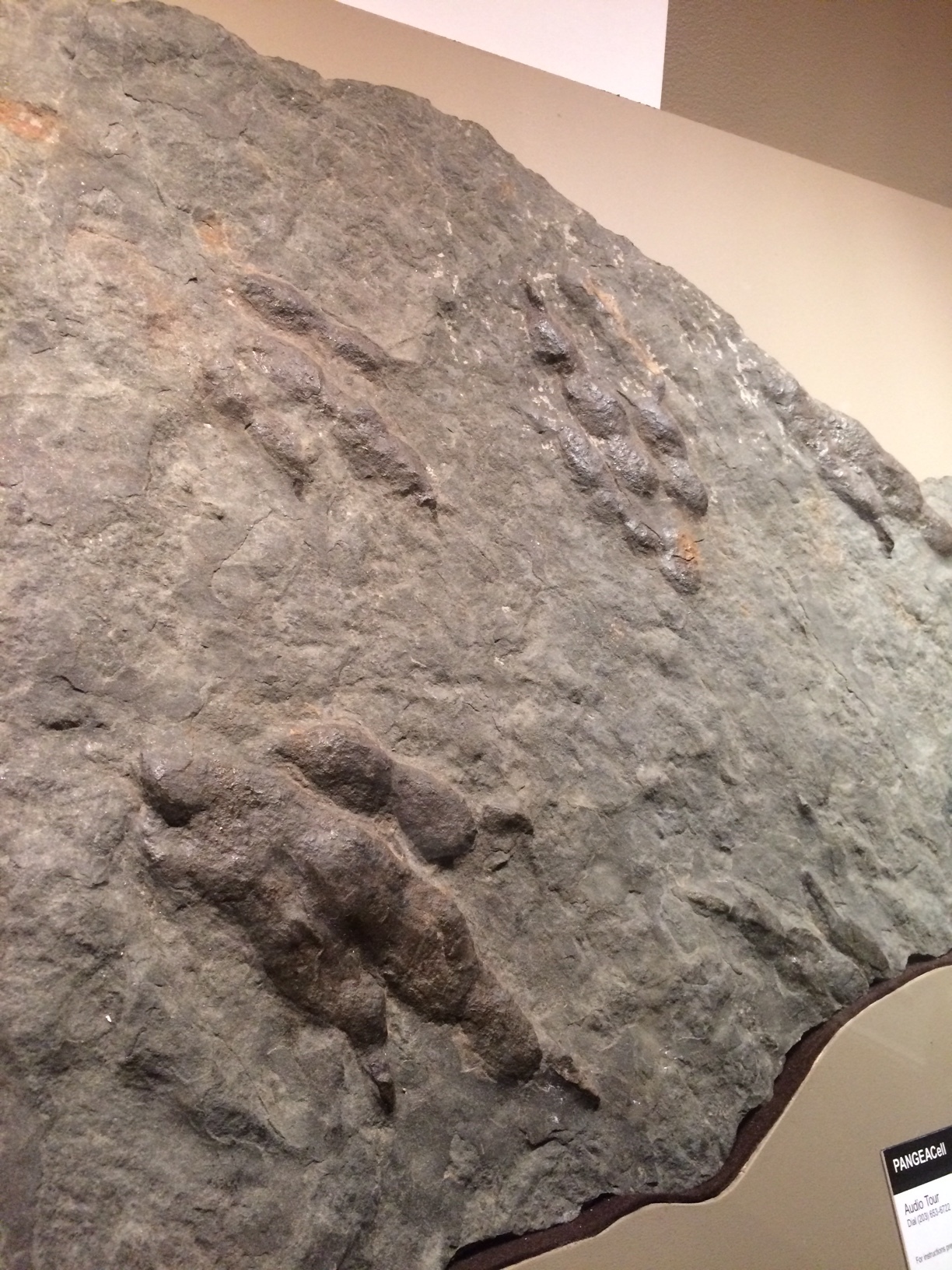

If you visit our newest science exhibit, Last Days of Pangea: In the Footsteps of Dinosaurs, you’ll see an amazing array of fossilized footprints displayed. These footprints come in all sizes: Some as small as a fingernail, some longer than the length of my forearm. Some are hazy and indistinct, clearly having weathered the forces of time and erosion. Others look like they could have been made yesterday. It’s much easier to imagine a tough and solid bone surviving millions of years than a single delicate footprint laid down in soft mud. How is it that these footprints made it from the Triassic to now? It takes just the right set of conditions.

Illustration by Kate Dzikiewicz

The first steps for making a fossil footprint are easy: Steps. A dinosaur or other animal walks through mud or damp sand and leaves tracks behind. Most footprints don’t make it any further into the geologic record. They get swept away by water, trampled by other animals, or damaged by any number of other forces.

Illustration by Kate Dzikiewicz

Next, the footprints are covered with a layer of sediment. Rather than destroying the tracks, burial gives them protection. Ideally, this occurs after the tracks already have had a chance to dry out and harden at the surface.

As years pass, the layers of sediment turn into stone. There are undoubtedly many fossil trackways trapped underground in this state. It takes a lot of luck for a trackway to be discovered. Some emerge at the surface when the rock layers covering them are eroded away. However, if the footprints aren’t discovered and protected in some way, they will eventually erode themselves.

Other times, tracks are found when they’re unearthed by digging. Connecticut is one of the best places in the world to find dinosaur footprints, so much so that they are sometimes discovered by accident. In August of 1966, a worker named Edward McCarthy was bulldozing the planned site of a new state building when he noticed something strange. One of the slabs of gray sandstone he’d just moved was covered in three-toed footprints!

Construction was halted and scientists were called in to examine the find. They quickly identified the footprints as dinosaur tracks. Rather than a state building, officials decided to make the site a state park instead. They cleared a wide swath of dinosaur footprints and built a building over the area to protect them, making it one of the largest displays of dinosaur tracks in the world. Dinosaur State Park is only about an hour from the Bruce Museum and is well worth a visit.

There’s something else you that you might notice when browsing the footprints of Last Days of Pangea. Some tracks sink into the rock, as you might expect from a footprint (left image). Others stick out from the rock, like three-dimensional replicas of dinosaur feet (right image). Both are fossil footprints, but their preservational mode is different. If a fossil track is indented into the rock, it is called a true track and represents the actual footprint of the dinosaur. If the footprint is three-dimensional, it is the natural cast of a footprint, created when sediment filled in the true track and hardened into rock.

Illustration by Kate Dzikiewicz

The tracks of modern dinosaurs, also known as birds.

Photo by Alison Rawson

Fossil trackways are fascinating enough on their own, but we can also use them to learn more about the animal that made them. The distance between one footstep and another can tell you how fast an animal was moving. If multiple trackways are found all heading in the same direction, it might mean the animals were herding. Smaller sets of tracks next to larger ones indicates parental care. One particularly interesting fossil we looked at while selecting tracks to display showed the impression of a dinosaur sitting down in the mud. You could see the feet and rear of the dinosaur, and around the dinosaur rump there were the impressions of feathers. This fossil was one of the earliest pieces of evidence for feathered dinosaurs, though it took years before its significance was recognized.

There is one thing that tracks can’t tell us: Species. We can compare footprints to bones to tell generally what sort of dinosaur made what sort of track, but it’s almost impossible to know which exact species the track belongs to. A song sparrow and a chickadee lay down very similar footprints but are quite different species otherwise. While the tracks found in Connecticut and our exhibit seem like they might belong to Dilophosaurus and Coelophysis, no one can say for certain. For that reason, tracks are assigned their own species names, called ichnospecies. So a footprint that came from a small three-toed dinosaur would be called Grallator. Maybe Grallator was made by Coelophysis, maybe not, but they are still very interesting to look at either way.

- Kate Dzikiewicz, Paul Griswold Howes Fellow